By Vladimir Shopov

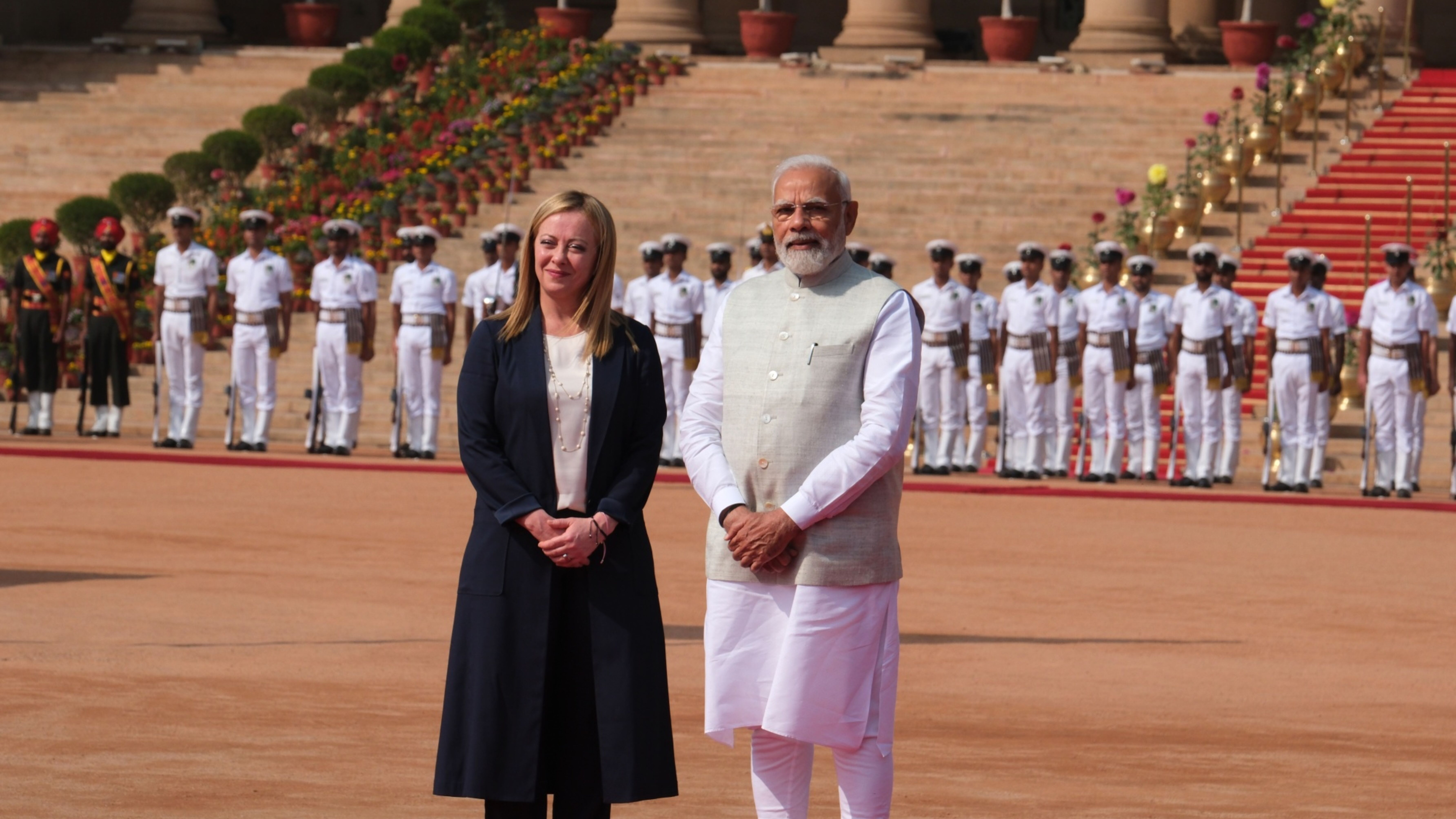

Something unexpected happened at the recent G20 meeting in Bali, Indonesia. The traditionally careful Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, indulged in strong diplomatic language after talks with the US president, Joe Biden. Instead of the usual balancing rhetoric, New Delhi welcomed the "continued deepening of the India-US strategic partnership," especially in "critical and emerging technologies, advanced computing capabilities, and artificial intelligence." Modi also paid special attention to cooperation under the QUAD (India, US, Japan, and Australia) format and the I2U2 (India, US, Israel, and United Arab Emirates) initiative, which other countries are yet to join.

In the evolved strategic culture of the Indian political elite, such behavior is no accident and is a distinct geopolitical sign. A few more recent events give density to what is happening. Just weeks ago, the US and India launched an institutionalized bilateral initiative for cooperation in critical and emerging technologies. It includes joint projects in military and other innovations, artificial intelligence, manufacturing circuits for microchips and other elements, space research, next-generation telecommunications, etc. New Delhi is also increasingly buying arms from the US, intending to shrink Russia's influence in this sector. In just two years, Russia's share of the Indian military market has declined by almost 50%. In turn, India's recently enacted military purchase fund of over $10 billion will be used to pivot away from Russia further and toward the domestic military industry.

However, the abovementioned transformation does not mean abandoning India's established status as a non-aligned country. This foreign policy concept's political and social roots are decades old and deeply institutionalized. They have their historical motivation, broad public support, and economic structure. The country's claim to be a civilizational state further strengthens its independent position. Concerning the war in Ukraine, neutrality is maintained. But the conditions in which such established approaches worked are gradually disappearing.

The deep divide between the West and autocracies like China and Russia makes balancing increasingly difficult, and their growing aggressiveness demands more detailed responses. Just a few years ago, Beijing again initiated a limited military clash with New Delhi along the disputed northern border. On the other hand, China's Belt and Road Initiative have flown into South Asia and countries like Sri Lanka, which the Indians treat as their reserved sphere of influence. China's accelerated military investments and increasingly frequent maneuvers in different seas and oceans have created an acute sense of strategic vulnerability, especially after Narendra Modi came to power in 2014. The most active part of the recent globalization wave has largely passed India due to protectionism, perception of self-sufficiency, and delayed institutional and infrastructural development. Now, however, collectivist autarchy as an economic model is breaking down. Moreover, partial de-globalization provides new opportunities for the country as a host of industries and companies have initiated a process of geographical and market diversification.

For decades, India rightly promoted itself as the world's largest democracy, an example of multiple cultural and linguistic communities coming together. The Gandhian political dynasty and the long dominance of one party suggested the limitations of such a description, but Narendra Modi's coming to power almost a decade ago launched a more frequent shuffling of basic democratic procedures. The list of changes has grown over the years to include pressure on civil society, restrictions on media freedom, persecution of journalists, support for social business elites, suppression of attempts to investigate Modi's actions as chief minister of Gujarat state, increasing pressure and violence on Muslims, and more. It is no coincidence, therefore, that organizations such as Freedom House and the V-Dem Institute now classify the country as a 'partially free democracy' and even an 'electoral autocracy.'

Recently, New Delhi used emergency laws to block YouTube and Twitter videos and links to a critical BBC documentary that asked uncomfortable questions about the current prime minister's political past. A few months ago, a director of the company FaceTagr boasted that their facial recognition software was now being used daily and in all sorts of situations by local police. Two years ago, the opposition Congress Party accused Modi of illegally tracking over 300 politicians, business people, journalists, and even ministers through Israeli software.

But it is the Indian prime minister's economic reforms that have more immediate consequences. Broadly, he has set about the gradual and still partial dismantling of a quasi-socialist, highly protectionist, and self-sufficient economic system. Much has been done in recent years. Examples include the reduction of corporate tax to 25 percent, opening up important sectors to foreign investment such as military production and finance, an ambitious investment program in infrastructure, a uniform value-added tax for the country, creation of the Make in India program, reduction of regulations and administrative reform, building digital infrastructure, investment in high technology and others. Quite predictably, many elements of the past and changes that have barely begun remain. For example, New Delhi continues to stand on the sidelines of regional free trade agreements, though there is some movement here, at least in the thinking of Indian elites.

Further simplification of the tax system is needed. The state has a majority stake in too many banks, there remain regulations on where they can invest much of their capital, and there are numerous restrictions on foreign companies access to various sectors, etc. Nevertheless, more and more companies are turning their eyes to the country, and landmark investor like Apple is launching new industries. In the coming years, the inflow of foreign investment will increase manifold.

For many years, behind the thesis of Asia's rise in the 21st century, there was an insistence that this was actually about China's awakening and its positioning at the center of the global economy and politics. In other words, the Asian century was Chinese. However, this picture is beginning to change. , the Asian century was the Chinese century. However, this picture is beginning to change.

Beijing is mired in several crises, its clash with the West creates further uncertainty, and the country has become an autocracy. More and more countries are worried about Chinese aggression and looking for political and economic diversification. Alongside this, India itself is building up arguments in its favor. It has already surpassed China in population and has a much better demographic trajectory, is accelerating its integration into the global economy, is opening up a new horizon for growth and development in Asia, and is getting involved in more and more regional and international organizations. Many future industries are gaining momentum there, and the country is also gaining cultural influence and position.

It has long been clear that Asia's return to the global political and economic map will not be a function of any one country, not even China. But for long periods, such a development indeed seemed possible. With the rise of India, such a scenario now seems out of the question. However, it is up to New Delhi exactly how far its influence will reach.

THE BOTTOM LINE For decades, India has rightly promoted itself as the world's largest democracy, an example of reconciling multiple cultural and linguistic communities